“We are not educated people, but I can sense something grave is happening around us. I couldn’t believe my eyes – the land that I had tilled for years, that fed me and my family for generations, has vanished. We have lost our livelihood. All our belongings and cattle were swept away by cyclones. We have moved to Sagar Island and are trying to rebuild our lives from scratch. It wasn’t like this when I was young. Storms have become more intense than ever. Displacement and death are everywhere here. The land is shrinking and salty water gets into our fields, making them useless. We feel very insecure now.” Tulsi Khara, 70, India

Within this region climate change is predicted to increase the frequency and intensity of disasters such as the rise in sea level (resulting in the loss and salinisation of land), storm surges, cyclones and typhoons, riparian flooding, and water stress. In India, large populations already live in areas vulnerable to flooding and by 2050 it is anticipated that 1.4 billion Indians will be living in areas experiencing the negative effects of climate change. Several highly populated mega cities of South Asia – Dhaka in Bangladesh, Kolkata, Mumbai, and Chennai in India – are especially vulnerable to a rise in sea level.

“Climate change has wrecked everything; our people are living in other towns and cities, like refugees. All I wanted was to grow old with my children and their children. But now they are gone and I don’t think they will ever return.” Shamisur Gazi, 83, Chakbara, Bangladesh

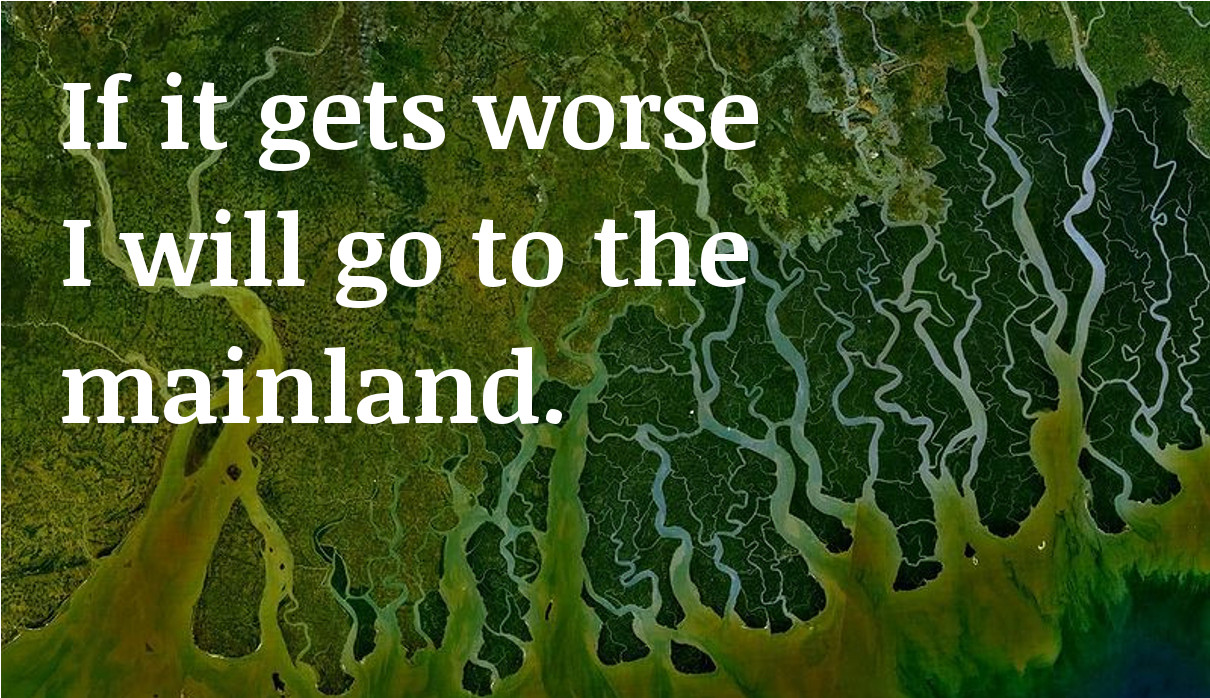

“God knows how long this village will last. If it gets worse I will have to go to the mainland. We know the end is coming.” Jakir Hossain, Fisherman, Bangladesh

“The sea water is rising every day … We lost everything. We are not happy, because we must move again. Climate change is making thousands of people homeless.” Nurul Hashem, Schoolteacher, Bangladesh

Within this region climate change is predicted to increase the frequency and intensity of disasters such as the rise in sea level (resulting in the loss and salinisation of land), storm surges, cyclones and typhoons, riparian flooding, and water stress. In India, large populations already live in areas vulnerable to flooding and by 2050 it is anticipated that 1.4 billion Indians will be living in areas experiencing the negative effects of climate change. Several highly populated mega cities of South Asia – Dhaka in Bangladesh, Kolkata, Mumbai, and Chennai in India – are especially vulnerable to a rise in sea level. In Bangladesh more than 50 million people live in poverty and many of these live in ecologically vulnerable areas such as floodplains, coastal zones or river islands. Bangladeshi communities face both sudden-onset climate related disasters (floods, river erosion and cyclones) and slow-onset disasters (coastal erosion, sea-level rise, salt water intrusion, rising temperatures, changes in rainfall and drought).

“The land here used to be 1 km out to sea … We lost mosques, a school, shops, farms. We are scared of the sea now. Gradually it comes closer to our homes. When we sleep, we are scared. Every year the tide rises more and comes in further. Next year this village may not exist.” Mohamed Rashed, Qumira Char, Bangladesh

Recent disasters in South Asia demonstrate what could be a more frequent reality for the region. Floods in September 2012 displaced 1.5 million people in the northeastern state of Assam, India while Cyclone Alia, in 2009, displaced 2.3 million people in India and almost 850,000 in Bangladesh. Extreme climatic events have placed greater stress on health services, agricultural production and water resources.

The region is identified as a ‘hotspot’ whereby greater exposure and sensitivity to climate change is combined with limited adaptive capacity, causing the former to have a more exaggerated impact. Factors that restrict the region’s ability to adapt to climatic change include the density of the population, multiple existing natural and human-induced stresses, the range and variety of climatic events and, in the case of Bangladesh, limited scope for internal inland migration.

This mega-delta has traditionally experienced significant flows of internal and international migration. Whilst there are many drivers of migration, it is clear that slow- and rapid-onset disasters continue to affect migratory patterns, although predicting the extent of the impact is a difficult. For decades, Indian and Bangladeshi communities have been supported by money transfers from workers abroad. The sums involved are vast and in the case of Bangladesh the income received exceeds international aid and foreign investment. The extent to which this important income could be affected is unknown but it could have a devastating effect upon poorer communities who rely upon such remittances.

In Bangladesh most environmentally-induced forced migration, such as by floods and cyclones, is met with local, short-lived internal displacement. Where the majority of people are able to return to their homes quickly the impact is more limited. However, this is not always possible, as was the case after Cyclone Alia. Planning migration in areas where climate change is degrading land could provide a safety net for large swathes of the population in this region, thereby helping to ensure that livelihoods are protected.

Alex Randall

Testimonies from:

Aulakh, R, 2013. How bad can climate change get? Bangladesh already knows. The Star (Bangladesh) 09 February.

Vidal, J, 2013. Sea change: the Bay of Bengal’s vanishing islands. The Guardian (UK), 29 January.

WWF India – Climate Witness stories. 2013. WWF India – Climate Witness stories. [ONLINE]

Sources

Asian Development Bank, 2012. Addressing Climate Change and Migration in Asia and the Pacific. 1st ed. Manila: ADB.

Walsham, M, 2010. Assessing the Evidence: Environment, Climate Change and Migration in Bangladesh. 1st ed. Geneva: IOM.

Provost, C. “Migrants’ billions put aid in the shade” The Guardian, 30 January 2013.

Facebook cover photo: NASA / Wikimedia Commons.

This is so concerning. The plight of the people of Bangladesh, who are very densely living in an ongoing ecological disaster.